Daring to Trust

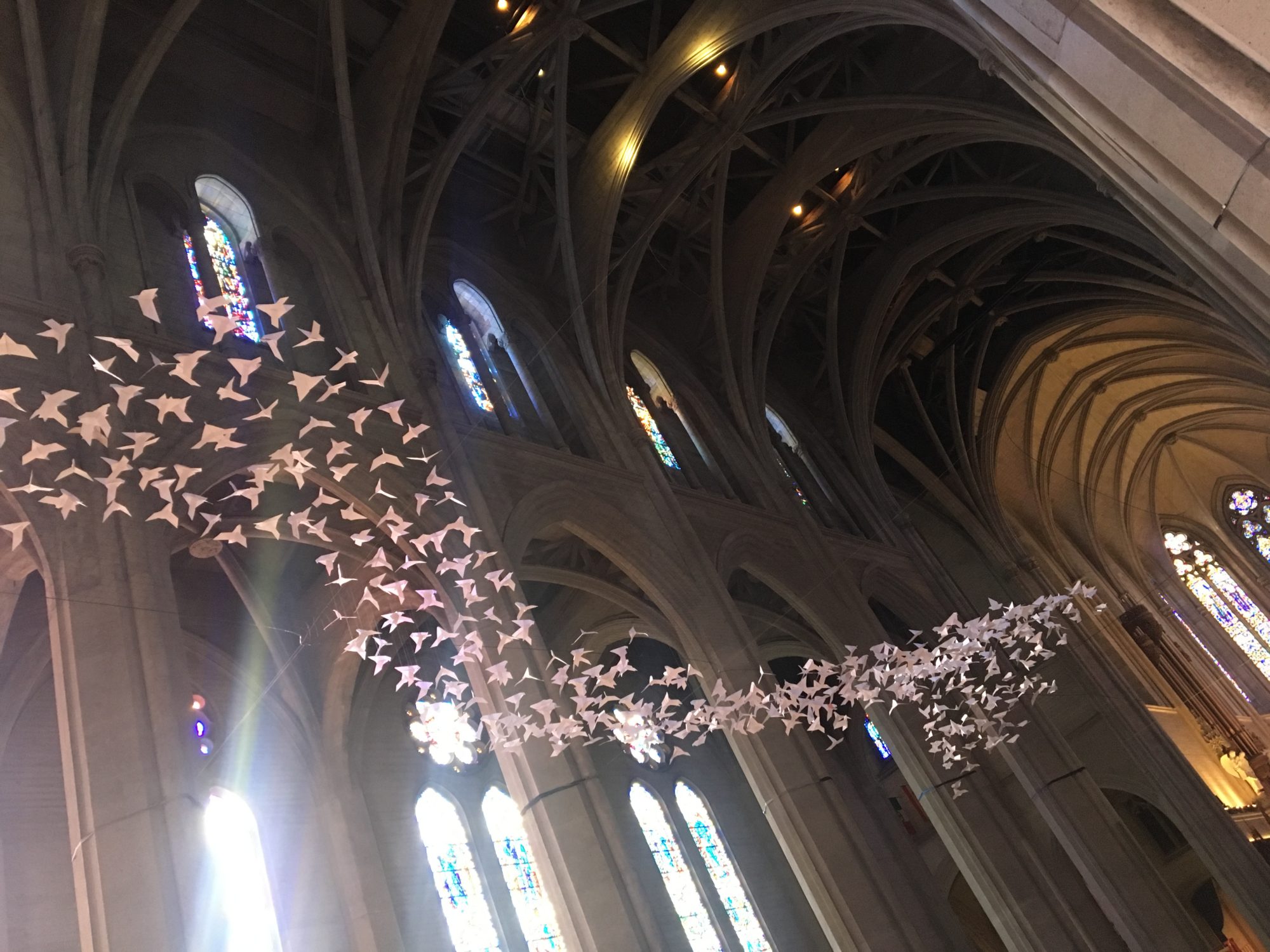

A sermon preached at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco on Sunday, January 26th, 2020 (Third Sunday after the Epiphany, Year A)

Readings: Isaiah 9:1-4; Psalm 27:1, 4-9; 1 Corinthians 1:10-18; Matthew 4:12-23

Of all the big, broad, spiritual virtues that Christians are exhorted to embody, my least favorite by far is trust. I mean, I like it fine in theory. Intellectually, I can appreciate why it’s virtuous. But when it comes time for me to actually apply it, you can find me busily constructing a detailed, well-documented outline about why trusting is for other people, not for me. You can glean a great deal about your character flaws by the advice that different people in very different areas of your life keep giving you. If I had a dollar for every time that somehow has said, “You know, Kristin, you just need to trust,” I would be a very rich woman.

Trusting is hard. It requires that we let people in. That we relinquish control – sometimes completely – and let someone else be responsible for what is most precious to us. Our well-being, our families, sometimes even our lives. Trusting requires us to be ok with not having all the answers or knowing what the next step is. It requires us to stop fretting about the future and be fully in the here and now. And, for many of us, that goes against everything we’ve been taught about how to succeed, or even just survive, in this highly individualistic society. Trusting is no mean feat. And yet, God calls us to trust again, and again, and again.

The call of the first disciples is not usually celebrated as one of Jesus’ miracles, but I think there is something miraculous about this story. It is not at all a foregone conclusion that Peter, Andrew, James, and John said yes to Jesus’ rather unusual invitation to come and follow him. The trust required for these four disciples to leave their possessions, their livelihood, their families and follow a stranger who offers them no information whatsoever about who he is or what is to come is…staggering. They were risking everything. In a world where we invest considerable effort in teaching our children not to wander off with random strangers, this Gospel story is downright unimaginable for many of us.

So what are we supposed to draw from this story? That we should throw caution to the winds and drop everything to follow the next raving sidewalk preacher we encounter? I sure hope not. That we should leave our family obligations without a backward glance so we can devote our lives to fishing for people? That’s certainly what Jesus called the disciples to do, but I don’t think that’s the universal takeaway either. This story is often used as a rousing call to evangelism, and it is that. But I think, even more foundationally, it is a call to trust. To leave behind, not just the security of our possessions and the comfortable routine of our lives, but the need to be in control. To agree to follow, to be guided, to let someone else lead us.

When Jesús invited his first disciples to follow him, he wasn’t just inviting them to trust him. He was also inviting them to trust one another. To build a community of mutual interdependence that we see at work throughout the Gospels. Today, as our Cathedral community gathers for our annual meeting, how might we live into Jesús’ invitation to deepen our trust in God and in one another? Do we really trust each other? Do we really know each other? Are we really in this together? How could we grow in trust?

Following Jesus isn’t something we can do alone. The closer we draw to God, the closer we draw to each other, into the messy, beautiful, holy reality of a community of trust. I admit to you that I’ve been binge watching the new netflix docu-series, Cheer, which, if you haven’t seen it, is a behind the scenes look at one of the nation’s top collegiate cheerleading teams. It’s fascinating on many levels, but what most struck me is how foundational trust is to everything the team does – unsurprising in a sport that literally involves throwing people in the air and then catching them. Every time these athletes let a teammate fall to the ground, uncaught, they immediately, without prompting, drop to the ground and do 50 push ups. Because they know that failing to catch a teammate is the worst offense imaginable, not just because of the potential for serious injury, but because, when trust is absent, success is impossible.

I’m not suggesting that the Church adopt push-ups as a form of penance, but what if we as a community took trust that seriously? What if we were deeply committed to catching each other when we fall, to lifting each other up, to having each other’s backs no matter what? What if we trusted each other enough to not always need to be in control, to follow each other’s lead, so that we can do the work that Jesus calls us to do – teaching, healing, sharing the good news with a world in need? In this season of light, what if we allowed ourselves to trust? Amen.